Art of the Anglo-Saxon and Vikings -

Part 3: Insular Art

-Dr Andrew Thompson

In Part 1 of this series we discussed the rudimentary decorative styles which were used by craftspeople throughout the Migration Period and "Viking Age" to decorate everyday objects, while, in Part 2, we discussed the origins and evolution of animal style art (glossed as Salin Style I and II) which dominates the sophisticated archaeological material of the Early Anglo-Saxon period in Britain, and of contemporaneous Germanic tribes across North and western Europe.

In Part 1 of this series we discussed the rudimentary decorative styles which were used by craftspeople throughout the Migration Period and "Viking Age" to decorate everyday objects, while, in Part 2, we discussed the origins and evolution of animal style art (glossed as Salin Style I and II) which dominates the sophisticated archaeological material of the Early Anglo-Saxon period in Britain, and of contemporaneous Germanic tribes across North and western Europe.

While this evolution of so-called "Germanic" art had been taking place, so-called "Celtic" art had continued to flourish and evolve, in a degree of isolation, in Ireland and the fringes of Britain. Cross-fertilisation of art between the "Germanic" world and the Hiberno/Celtic/Brythonic one appears to have been limited, following the Western Roman Collapse and on into the 7th century. However, as the elite of the emerging Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in Britain converted to Christianity in the 7th century, strongly under the influence of Irish missionaries, a new cultural bridge was formed between these two very different artistic cultures. The result, in the 8th century, would be some of the most spectacular art in European history...

"Celtic" influence is not entirely absent in the archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England prior to the explosion of insular art, and it is instructive to examine the few cases where such influence is evident.

Swirling Escutcheons / “Trumpet Spiral”

Existing outside of Salin’s classification of Animal Art must be mentioned a quite distinct artistic style which first emerges, in England at least, on the elaborate enamel escutcheons decorating hanging bowls. While the hanging bowls of the 6th century come from diverse contexts and display either overtly late Roman decoration, or else rather peculiar openwork escutcheon designs (Bruce-Mitford Group A), in the 7th century, new styles of hanging bowls emerged (Bruce-Mitford Group B and C) which have exotic-looking, champleve enameled copper-alloy escutcheons with swirling patterns previously absent from Anglo-Saxon art, and for which the best analogue is the 8th century Irish Book of Durrow, and the probably Kentish Stockholm Codex Aureus. |

| 7th century hanging bowl escutcheon from King's Field, Faversham. (C British Museum) |

|

| 7th century hanging bowl escutcheon (unknown provenance, C British Museum) |

|

| Stray hanging-bowl escutcheon from Royston Grange, Matlock, Derbyshire, showing 'Anglian' bird heads integrated into the trumpet-spiral design. |

|

| Escutcheon from the hanging bowl from the 7th century burial mound at Benty Grange, Derbyshire, showing serpentine biting-beasts integrated into the enamel-work. |

While there is some evidence for similar work in Scotland and Ireland, similar finds are, curiously, entirely absent from Wales and Cornwall. The function of such bowls is not known, in the 7th century they become particularly associated with high status "warrior chief" burials and may have been diplomatic gifts from "Celtic" regions. While these more broadly represent an early instance of the early Anglo-Saxons in England appreciating "Celtic" style art, those curious cases where "trumpet spirals" are combined with emphatically "Anglo-Saxon" motifs suggest that these esceutcheons represent the first tentative steps towards insular art in England (discussed later) - the influence of ‘Celtic’ art styles arriving simultaneously with the Anglo Saxon kingdoms’ adoption of Christianity.

Late Salin Style II

As the 7th century wore on, and perhaps with a degree of influence from "Celtic" interlace designs, Anglo-Saxon animal art became more sinuous, with a greater influence on the knotting of long bodies, the "biting beast" motif, and a greater variety of beast head forms. The picture is complicated by a number of "retro" phases, with old-fashioned motifs briefly coming back into vogue, but overall the trend was towards greater sinuousness, and greater diversity, to some extent foreshadowing, and to some extent paving the way for the explosion of diversity in Scandinavian animal art under similar circumstances (to be discussed in the next chapter).From 700 CE or thereabouts, animal art is occasionally glossed as "Salin Style III" - referring collectively to this trend towards greater complexity, with more delicate and intensely interwoven forms. Middle to late Anglo-Saxon animal art is sometimes included in Style III, and sometimes not - a fact which hints at the vagueness and limited usefulness of this category. In fact, the growing diversity of animal art across Western Europe and Scandinavia, partly enhanced by the emergence of Insular Art under "Celtic" influence, and to some extent, influence of Byzantine and Coptic Art from the East, means it is no longer useful to refer to a general Germanic art style.

Insular Art

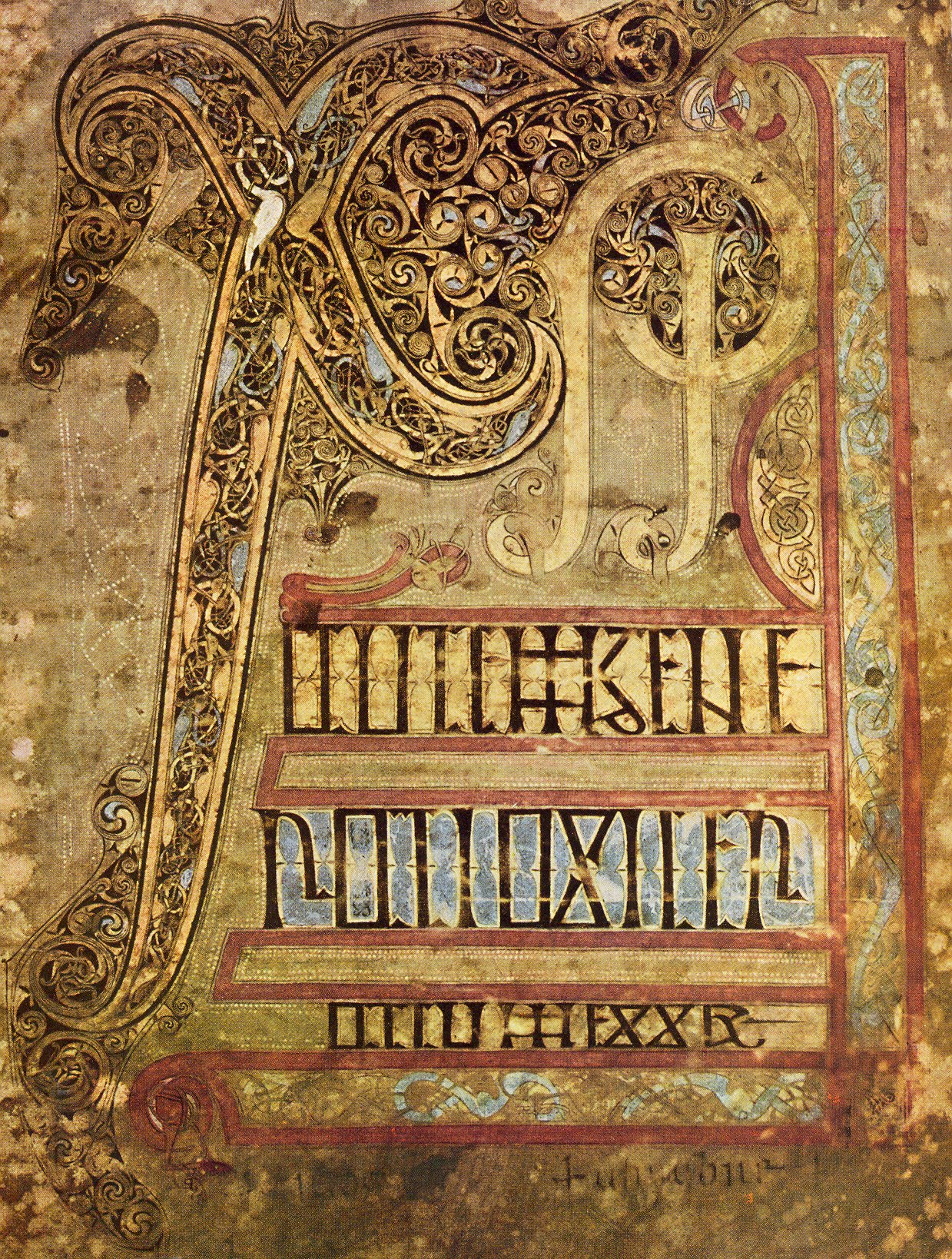

By 700 CE, the cross-fertilization of art between the Anglo-Saxon and "Celtic" kingdoms across the British Isles had led to a flourishing of increasingly exquisite art, particularly religious art, best exemplified by the spectacular illuminated manuscripts produced in the early 8th century - the Lindisfarne Gospels, Lichfield Gospels, and in Ireland, famously, the Books of Kells and Durrow. The term "cross-fertilisation" is carefully chosen, here, because while "Celtic" art was influencing artwork in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, art of widely recognised Celtic craftsmanship, particularly in Scotland and Ireland, were increasingly integrating aspects of Anglo-Saxon animal art. |

| Folio 192 of the Book of Durrow, 650-700 CE. (Scriptorium disputed - either Durrow, Iona, or Northumbria). Dominant motifs are of biting beasts and late Style-II interlace. |

The emphasis, previously on personal artworks of intricate metalwork, now shifts to ecclesiastical items, and media including illuminated manuscripts and stonework. This is, partly, as examples of art in these media begin to emerge around this time, but also due to the decline of the furnished burial rite, in Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, as a result of Christianisation during the 7th century. As a result, the corpus of personal artworks from the middle Anglo-Saxon period is much poorer than before, although the combined efforts of the Portable Antiquities Scheme and armies of metal detectorists are beginning to change this, with more and more mid Anglo-Saxon material (often subject to accidental loss, and therefore not concentrated in archaeological sites) emerging. The overall picture from such finds is that the decorative styles deployed on personal artworks of the 8th century are broadly consistent with the stylistic developments of insular art seen on other media.

The tale of the Insular Artistic Style in some ways mirrors the rise and decline of the dominant kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England, with first Northumbria, then Mercia and finally Wessex being in the ascendant both politically and culturally.

The Hiberno-Saxon (or Northumbrian) subset of Insular Art is exemplified by the densely patterned ‘carpet’ pages found in mid Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts.

|

| Shoulder clasp from Sutton Hoo Mound-1, early 7th century showing decorative styles analogous to, and directly foreshadowing insular art of the late 7th-8th centuries |

It also gets inspiration from ‘Celtic’ curvilinear trumpet and hair-spring spiral motifs and sometimes uses processions of interlacing long-jawed beasts which have clearly evolved from Anglian Style II metalwork examples.

This art-form arises in England in the 7-8th century. There are notable carpet pages in the Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels, Book of Durrow but one of the most striking examples is that in the Lichfield Gospels book, which is dated to 730 CE and which is probably native to Mercia.

It has patterns of interlaced birds on the cross-carpet, which resemble the ornament on a cross-shaft from Aberlady, Lothian. In the mid 8th century, this was a Northumbrian site on the direct route between the monasteries of Iona and Lindisfarne, linking the Lichfield book with Lindisfarne.

The fully developed style comprises a profusion of birds, dogs and other animals, complex ‘Celtic’ spirals, cell-work grids and punctilious interlace-work, all carefully framed. It is likely that this elegant form of ornamentation was produced for other than purely aesthetic reasons; in that it probably carried a spiritual message, of a complex divinely ordered world, which was emphasized by repeated use of the cross as a motif and of the Chi-Rho.

Traditionally, metalwork in Anglo-Saxon period from 700 CE onwards has been regarded separately from the ecclesiastical artistic developments in the scriptoria of Ireland, Northumbria, Lichfield and Kent. However, it is quite clear that evolution of each of these spheres of art did not occur in isolation. In what would later become Anglo-Saxon England, under the umbrella of Insular Art, the popular Anglo-Saxon animal styles developed into the so-called Mercian Style (defined by sinuous animal interlace) in the 8th century and then into the Trewhiddle Style in the 9th century.

Mercian Style

As the fortunes of Northumbria declined in the 8th century, the ascendant kingdom of Mercia became the new focus of artistic innovation. A new and distinctive animal art style began to appear in Mercian manuscripts, sculpture and metalwork. This combines a fairly consistent range of animal, plant, swirling patterns and abstract motifs.The latter can, quite clearly, be seen to be descendent of the trumpet-spiral escutcheons which began to arrive in the 7th century. The animals, often lizard-like, appear in interlace or among the stems and berries of vine scrolls and other plants. A good example is the Witham Pins (British Museum), the middle disc of which has panels filled with winged animals with lightly incised collars and other body markings enmeshed in interlace.

|

| The Dalby Mount - a possible late 'sword pyramid' - Silver gilt, showing classic Mercian-style decoration, found in Leicestershire in 2011. (CC Portable Antiquities Scheme) |

Another example is the whalebone Gandersheim Casket, which was made in southern England in the late 8th century, and is decorated with an intricate set of interlacing creatures, vine-scroll and spiral ornament.

|

| Gandersheim Casket, late 8th century, decorated with an intricate set of interlacing creatures, vine-scroll and spiral ornament again consistent with so-called "Mercian Style". |

A prominent feature of Mercian Style, and closely related to the new style of manuscript art, was the use of three dimensional animal-heads as features in their own right, equipped with sharply toothed gaping jaws and lolling tongues. Examples include the Westminster seax-chape and the animal-headed sword-chapes from the St. Ninians Hoard, both of which date to the 8th century. The gold ring found at Berkeley Castle and the stone-carved versions at Deerhurst are further examples. Whole animals often feature erect wings and tails twirling into knots.

|

| Seax-chape from Westminster, mid-late 8th century. |

The style has some variants but a common theme is that of seemingly energetic spotted animals enmeshed in fine looping interlace. This is the dominant ornamental style of the secular metalwork of the Mercian supremacy, typified by the brooches and pins from such high status sites as Brandon, Suffolk and Finborough. However, the most spectacular examples must be associated with elite weapons such as the outstanding silver-gilt and niello-inlaid sword pommel, hilt and upper grip found in Fetter Lane, London.

This is dated to the later 8th century and is decorated with a tendril pattern, bird heads, a beast and a distinctive swirling spiral of four serpents. Other examples include the sword pommel found at Royal Oak Farm, Beckley, Oxford and the scabbard chapes and pommel from St.Ninian’s Isle.

| ||

| Beast-head on a chape from St Ninian's Isle Hoard. Two such chapes, four brooches, and an elaborate pommel all show so-called "Mercian Style" decoration. |

Trewhiddle Style

This refers to the style of late Anglo-Saxon art that flourished during the ninth century and is named after the Trewhiddle Hoard - a collection of gold and silver objects found by tin miners in a stream near St Austell.Some of the strap-ends and other fittings found there were decorated with distinctive animal designs.

|

| The "Aethelwulf" and "Aethelswith" Rings, both associated with the royal house of Wessex, both showing mature Trewiddle-style decoration in gold and niello. (C British Musuem). |

Of particular note are Trewiddle-style strap-ends which show up in great abundance from the early 9th century onwards. An unusual example of mature Trewhiddle style executed in gold is the finger-ring from Poslingford, Suffolk.

|

| Gold ring from Polingsford, Suffolk, showing late Trewiddle Style interspersed with plant-like motifs (late 9th century) (C. British Museum). |

Winchester Style

Primarily considered as a style of Manuscript illustration and ivory carving, it adapted well to metalwork and was characterised by openwork or high relief versions of the typical foliate and zoomorphic (acanthus, bird and beast) motifs. | |||

| Unprovenenced Winchester-Style belt-end (C British Museum) 10-11th century |

|

| Unprovenenced gilt-copper-alloy spouted jug, possibly for liturgical use, demonstrating early Winchester Style decoration interspersed with some atrophied animal-art elements. (C British Museum). |

|

| Mid 11th century reliquary cross (CC, V&A Museum) |

Aftermath

(Old English : æfter + mæþ, meaning literally ‘following a mowing’)By the end of the Anglo-Saxon period, English art was already being overtaken by more continental styles, but 1066 was a watershed for English art as the Anglo-Saxon elite who had been patrons of high art were either dead, fled or dispossessed. It is thus not surprising that Insular Art came to an abrupt end with the conquest - the new elite being patrons of more continental styles. The frenetic energy, freedom and love of complex interlace which characterised Insular Art had, though, already significantly influenced other parts of Europe, and would go on to influence the later Romanesque and Gothic art styles.

Meanwhile, in Scandinavia, while the distinctive Insular Art in England was dying, so-called "Viking Art" was reaching the peak of its sophistication - "Urnes Style", before it, too, was overtaken.

In the next chapter we look at the many, diverse "Viking" Art Styles, growing from Scandinavian varieties of Salin Style II in the 7th century, diversifying and flourishing up to the early 12th century.

References

Nielsen, K. H. (2010). Style II and all that: the potential of the hoard for statistical study of chronology and geographical distributionsBruce-Mitford, R. L. S., & Raven, S. (2005). A corpus of late Celtic hanging-bowls with an account of the bowls found in Scandinavia. Oxford University Press.

Hull, D. (2003). Celtic and Anglo-Saxon art: geometric aspects. Liverpool University Press.

Webster, L. (2011). Anglo-Saxon Art. London: British Museum.

Henderson, G. (1992). Anglo-Saxon Art. London, British Museum.

Brown, M. P. (2007). The Lichfield angel and the manuscript context: Lichfield as a centre of insular art. Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 160(1), 8-19.

Tweddle, D. (1983). The Coppergate Helmet.

Webster, L. (2005). Metalwork of the Mercian Supremacy. Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, 263.

O'Dell, A. C., Stevenson, R. B. K., Brown, T. J., Plenderleith, H. J., & Bruce-Mitford, R. L. S. (1959). The St Ninian's Isle Silver Hoard. Antiquity, 33, 241.

Wilson, D. M., & Blunt, C. E. (1961). III.—The Trewhiddle Hoard. Archaeologia (Second Series), 98, 75-122.

Kershaw, J. (2008). The Distribution of the ‘Winchester’Style in Late Saxon England: Metalwork Finds from the Danelaw. Oxford University School of Archaeology.

Ward, J. C., Laing, L., & Laing, J. (1980). Anglo-Saxon England. Britain before the Conquest series.

Turner, S., David, A., & Hamerow, S. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 22(2), 300

.jpg)